‘I have long ceased to invent…I wait till I seem to know what really happened. Or till it writes itself. Thus, though I knew for years that Frodo would run into a tree-adventure somewhere far down the Great River, I have no recollection of inventing Ents. I came at last to the point, and wrote the ‘Treebeard’ chapter without any recollection of any previous thought: just as it now is. And then I saw that, of course, it had not happened to Frodo at all.’

-Letter 180

Middle-earth is a curious place. So curious that even its author came upon unexpected things. A serious point of departure is the notion that the creation exists apart from its creator; the artist merely discovers it. That is for another blog, but it is, in a sense, literally true for Tolkien: Midgard, Middle-earth, midden-erd has been the description of the known world for much of northern European mythology. It is a place full of trolls, dwarves, hags, and other wondrous creatures…but those stories did not have tree people.

EXPLORE THE LEGEND

When we first meet Treebeard it is, not unlike Tolkien’s own discovery, quite happenstance. Merry and Pippin climb a stone hill in Fangorn to try and get the lay of the land and find a way out of the dense, labyrinthine wood. They hear a voice:

‘Almost felt you liked the Forest! That’s good! That’s uncommonly kind of you,’ said a strange voice. ‘Turn round and let me have a look at your faces. I almost feel that I dislike you both, but do not let us be hasty. Turn round!’

Ents are a curious people, tree-herders, the Onodrim, who can date their existence all the way back to the time before the arrival of the Children when the Valar played in the Blessed Realm. Aulë made his dwarf-children, the Seven Fathers of Dwarves, and knew that they would be great craftsmen and shape many things out of, you guessed it, trees. Yavanna, the mother of all that grows, was none too happy with her husband’s designs. She took her concerns to Eru, the One, and he created the ents to protect the trees for all time. They are, perhaps, trees with souls. Sadly the Ents aren’t as effective protectors as their ‘mother’ would have liked, but more on that later.

They woke up and learned the languages of Elves (‘The Speakers’) and enjoyed the days of Stars and Sun, the bounty of the world. Treebeard describes these days in his reminsescences to Merry and Pippin. Like so many verses of Middle-earth, it is a beautiful and sad song.

What can we learn about this curious person from his lament? Even if we don’t cipher the odd names and places he mentions, it is clear that he has been walking Middle-earth for a long, long time. However I think it will be interesting and insightful to break this poem down line by line and talk a bit about each place, the better to understand our treeish friend.

In the willow-meads of Tasarinan I walked in the Spring.

Ah! the sight and the smell of the Spring in Nan-tasarion!

And I said that was good.

Tasarinan and Nan-tasarion are the Quenya names for Nan-tathren, an ‘angle’ between the rivers Narog and Sirion in Beleriand, the West of Middle-earth in the First Age of the Sun. The standout is, of course, Treebeard’s use of Quenya. He seems to prefer it to the more widely used Sindarin, which is a brilliant move by Tolkien: Treebeard isn’t in on the goings-on of the world and would not know that Sindarin is the more fashionable and commonly used of the Elvish languages. It makes me think of a family I saw on a travel show in New Mexico: this family was the descendants of very early Spanish settlers in North America. Some how, through all the generations, they maintained their bilingual affiliations, speaking both Spanish and English. But, being isolated in the States, away from the rest of the Spanish-speaking world, their Spanish was antique, sounding to contemporary Spanish-speaking visitors like the King James of Spanish. This is how I imagine Treebeard’s usage of Quenya.

I wandered in Summer in the elm-woods of Ossiriand.

Ah! the light and the music in the Summer by the Seven Rivers of Ossir!

And I thought that was best.

Ossiriand is a bit easier. Even if we are not scholars of elvish languages, we see some roots and morphemes that should be recognized from the Sindar.

Tol Galen by Joseph Olonia

It at least ‘feels’ familiar. Rightfully so! Ossiriand is a Sindarin name for the region of southeast Beleriand where the seven rivers mingle. It was a land populated by a small colony of ‘Green-elves’, led by the first Denethor. It is also the land in which Beren and Lúthien retire to Tol Galen after their return from death.

To the beeches of Neldoreth I came in the Autumn.

Ah! the gold and the red and the sighing of leaves in the

Autumn in Taur-na-neldor!

It was more than my desire.

Neldoreth would be a prime destination for the forest sightseer. It is the southern part of the woods that make up the kingdom of Doriath and under the protection of Melian the Maia. If you’ve read the Silmarillion then you know that name, but then he throws us another curve ball with Taur-na-neldor. This appears to be a Quenya variant on the same name.

To the pine-trees upon the highland of Dorthonion I climbed in the Winter.

Ah! the wind and the whiteness and the black branches of Winter upon Orod-na-Thön!

My voice went up and sang in the sky.

And now all those lands lie under the wave

Dorthonion is another forested region in Beleriand that was briefly populated by the folk of Bëor, and Orod-na-Thon is a mountain of that region. Finally…

And I walk in Ambarona, in Tauremorna, in Aldalómë,

In my own land, in the country of Fangorn,

Where the roots are long,

And the years lie thicker than the leaves

In Tauremornalómeë.

Ambarona, Tauremorna, Aldalómë, and Tauremornalómeë are all other names Treebeard has given to Fangorn, his home. As I said in Ending And Failing, the Old Forest and Fangorn were once a singularly huge wood that covered much of Eriador, Dunland, and Rohan. But Hobbits and Dunedain and other Men have need of wood and paid no heed to forest. Its final remnant, Fangorn forest, is coveted by its keepers and when Saruman the White begins leveling its eaves for his own evil use, and when Merry and Pippin put the War in context for Treebeard, he wakes the shepherds of Fangorn and goes to war. Were this is an article on language we could break each of these names down and explore their meanings more, but I’ll suffice with a reference to Tolkien Gateway.

So what is the point of all of this? One, to inform and shed some light. Tolkien loved names but when they are presented in a plethora it can be confusing if we aren’t able to detach our desire to know from our appreciation of the linguistic aesthetic. Mostly, though, it is to show the ancientry of Treebeard. He has lived a long life, escaped the destruction of the First Age of the world, and spent his days enjoying the beauty of the woods in his charge. This song, more than anything (I would say even more than their famous moot) speaks to the character of the Ents. They will dwell long centuries on the beauty of ‘nut and acorn’, on the quality of leaves, the gentle beauty of the wind on branches. It is the already deep appreciation Tolkien had for trees, which was far deeper than most of our own, taken to the kind of believable extreme achievable only in fantasy. It is no wonder he and his people rise in wrath!

It is also indicative of the ‘greatness’ of Treebeard. Greatness, I mean, in the sense that he is the oldest, strongest, wisest living Ent. The rest of his people, at least the ones we meet, are in decline. Some are become treeish and no longer carry on their occupation as treeherds. Some are fearful and covetous, never leaving the remains of their meager herds. Some do not speak at all! Treebeard has kept his own language, along with those of the Elves and the Common Speech, and he has the wherewithal to see the greater needs of a world facing impending doom. Not only that, he also has the courage to raise his people up and, perhaps, save the western world (if not only Rohan)!

This theme is not uncommon in The Lord of the Rings, as a heroic tale: the characters we love are often the ‘best’ of their kind. Whereas the dwarves of The Hobbit are a bit greedy and cowardly, Gimli is brave and stalwart and an unfailing companion. The Wood-elves are often only concerned with their own realms and their parties, but Legolas shows grave concern for the entire world. All Rangers are tough customers, but Strider is ‘the greatest huntsman and traveler of the age’. Treebeard is much the same, a great leader of a people in decline.

Concerning Entwives, we know very little. In fact Treebeard, whom I have argued to be the greatest Ent living, does not remember much about them either! At a certain point the wives, caring more greatly for gardens and the smaller growing things (as opposed to trees and forests) decided to part from their husbands and go eastwards. The land where Treebeard suspects they ventured off too is now the blasted Brown Lands where nothing grows. But who was that tree-giant spotted by Sam‘s cousin Hal? Is it possible that the entwives wandered northwards into Eriador? I hope for a happy ending for the Ents before the world changes forever.

Entwife by Beth Godfrey

Some time ago I wrote a piece on Tom Bombadil, the centrality of which was his ambiguity and mystery. There is some of this with Treebeard as well. Gandalf says this of him:

‘The little that I know of his long slow story would make a tale for which we have no time now. Treebeard is Fangorn, the guardian of the forest; he is the oldest of the Ents, the oldest living thing that still walks beneath the Sun upon this Middle-earth.’

This is mysterious, though, as the Ents did not wake up until after the Elves. Treebeard himself, in his lore of living creatures, states that the ‘elf-children’ are ‘eldest of all’ (though the brevity of the list brings the zoology of Ents into question). Conversely, the Dwarves would be the oldest creatures as they were made first, but laid to sleep until the Elves awoke so as not to precede the true Children of Eru. Perhaps, then, this is conditional: the original waking Elves have all fled West or been killed since the beginning (though Galadriel left and came back…). The dwarves, being mortal, have suffered the same, and so, by sheer attrition, Fangorn is the oldest.

But what about Tom? ‘Eldest, that’s what I am,’ he says of himself. I would suggest that he does not count, being so mysterious and out of place and not, perhaps, ‘living’. He certainly did not make the cut on the Ents lore of living creatures. Many, including myself, have argued that he is a rogue Ainur, a creature of spirit, and so not counted among the ‘living’, those of only flesh and blood. His name in Elvish means ‘oldest and fatherless’. That in and of itself, I feel, discounts him from the list.

SHOWCASE THE ART

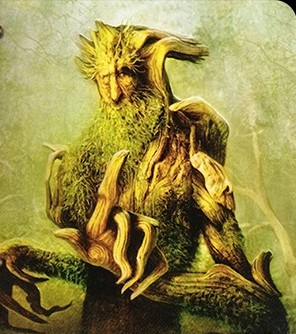

Though it raised some eyebrows after being spoiled at the top of the Ring-maker Cycle, Mike Nash‘s interpretation of Treebeard is just great. Treebeard, due to his vague description in the text (is it bark or skin or hide?), has been represented many different ways. Mr. Nash’s vision lands somewhere to the left of the Treebeard of the films, introducing a bit of abstraction: his hand, though it is in the foreground, seems a bit out of proportion as it wags at us, ‘Don’t be hasty!’ His face seems more treeish and less human. It also has a slight impressionist quality to it when one notes the lack of strong lines in the background.

This aesthetic of his is also apparent in some art he did for the Huorns of Into Fangorn. Huorns (and ents, really) fall somewhere along a spectrum between trees and monsters. Mr. Nash’s huorns lean towards monsters, which I think is a nice take on what has become a tired subject. For, as I said before, Tolkien’s description of Treebeard is rather sparse (he is often more interested in vivid descriptions of land, rather than people) and thusly Treebeard and other ents have either looked like trees with faces or giants with treeish qualities. This isn’t a problem, but has led to similar interpretations. I think the films did a good job of shaking things up and giving us a new take on Ents that clearly influenced this card.

As an aside, I think that Nash, along with Romana Kendelic, have provided some very fresh and fun art for our cards lately.

DISCUSS THE CARD

Treebeard has, rightfully, gotten a lot of attention since he was spoiled. He has very strong stats at a bargain-basement cost, especially in comparison to other unique neutral allies (like the Istari). He does have a slight downside in that he, like all Ents enters play exhausted and has a minor limitation on restricted attachments, but really it’s not that bad. Most of the really good attachments, restricted or no, already have some embedded restrictions like ‘attach to hero’ or ‘attach to Trait character’. But let’s talk about his usage.

To take full advantage of Treebeard’s abilities you’ll want him a Tactics/Lore deck to provide easy access to Wandering Ent and Booming Ent. The biggest restriction on Treebeard is that there is, to my knowledge, no shenanigan to move resources to an ally. So to get the most out of him, a card like Word of Command might be an option, provided you can draw it early, to fish Treebeard out of your deck and get him on the table to start collecting resources. Elf-stone is also nice to be able to play him for free.

That said, splashing Leadership would be a really good thing to do as well to take advantage of the readying and resource acceleration and mustering. A Very Good Tale or even Timely Aid can get him out for free and potentially early (just throw in three copies to up your chances). Even if you don’t splash Lore or Tactics getting Treebeard out quick will easily let him pay for your off-sphere ents since they are so wonderfully cheap. Aragorn is a nice option as well since you can tack on his accouterments to gain at least a Lore match to take some of the burden off of Treebeard.

In terms of theme, Ents make a good pairing with Hobbits. I love having these guys in my tri-sphere Hobbit deck, especially with Merry and Pippin and Treebeard in mind (stack their cards on top of Treebeard’s for added thematic enjoyment). Eagles and Silvan Elves are, I feel, another good match as they represent the ‘Wild’ and have some easy sphere matches as well.

Ents, including Treebeard, are a nice target for archery damage when Booming Ent comes into play. Three of them, plus Treebeard and three Wandering Ents, mean these puppies are attacking for a just-plain-gross 9 points of damage. Hard to pull of, but wonderful when you can make it happen.

How are you putting old Fangorn to use? Do you think we will see more Ents in the future to round out our march, perhaps in The Treason of Isengard? I leave you now with a bunch of links to all of The Tolkien Ensemble’s ent songs, which feature Christopher Lee as Treebeard. I’m not saying he would have made a better Treebeard than John Rhys-Davies…but he would have…I’m just saying…